Quân Lực

Việt Nam Cộng Hoà, một đạo quân đã chiến đấu dũng mãnh chống cả Khối Đế Quốc

Liên Xô, Trung Cộng và chư hầu để bảo vệ tự do, no ấm cho miền

Nam.(HsPblogspot)

Lời người

dịch: Bill Laurie là sử gia Hoa Kỳ, một

trong những chuyên gia nghiên cứu về Việt Nam và nhân chứng được mời trình bày

quan điểm trong cuộc hội thảo mang tên “Quân Ðội Việt Nam Cộng Hòa: Suy ngẫm và

tái thẩm định sau 30 năm” (ARVN: Reflections and reassessments after 30 years)

do Trung Tâm Việt Nam thuộc Ðại Học Texas Tech tổ chức tại Lubbock trong hai

ngày 17 và 18 Tháng Ba năm 2006.

Trong số nhiều diễn giả Việt-Mỹ, ông Laurie là người nêu ra quan điểm của riêng ông về một quân đội mà ông từng sát cánh với cương vị một chuyên viên tình báo cao cấp trong nhiều năm. Bài này được chuyển ngữ từ nguyên bản bài viết của Bill Laurie, mà ông dùng để trình bày, vắn tắt hơn, trong buổi hội thảo. Bill Laurie gửi tặng bài viết cho dịch giả, cho phép được dịch và phổ biến trong giới truyền thông Việt ngữ. Những chữ viết ngả để trong ngoặc đơn là chú thích của tác giả để câu văn chuyển dịch mang được đầy đủ ý nghĩa của nó.

----------

Quân Lực

Việt Nam Cộng Hòa thay đổi một cách đáng kể cả về số lượng lẫn phẩm chất trong

khoảng thời gian từ 1968 đến 1975. Sự thay đổi không hề được giới truyền thông

tin tức (Hoa Kỳ) lưu ý, và nhìn chung thì đến nay vẫn không được công chúng Mỹ

biết đến, vẫn không được nhận chân và mô tả đầy đủ trong nhiều cuốn sách tự coi

là “sách sử”. Một phần nguyên nhân của sự kiện này là do bản chất và tầm mức

của sự thay đổi không dễ được tiên đoán hay tiên kiến, dựa trên hiệu quả hoạt

động và khả năng của Quân Lực Việt Nam Cộng Hòa trước năm 1968.

Bài này

không hề muốn chối bỏ những vấn đề nghiêm trọng đã hiện hữu, hay phủ nhận rằng

vấn đề tham nhũng, lãnh đạo kém cỏi không tiếp tục gây hiểm họa cho khả năng

của Quân Lực Việt Nam Cộng Hòa bảo vệ đất nước họ. Tuy nhiên, ở một mức độ nào

đó, những vấn đề này có được giải quyết, và những khía cạnh tích cực của Quân

Lực Việt Nam Cộng Hòa không thể bị xóa khỏi trang lịch sử vinh quang.

Tôi đã tự

chứng nghiệm điều này, khi đến Việt Nam cuối năm 1971 và phục vụ 1 năm tại

MACV(Phái Bộ Quân Viện Hoa Kỳ tại Việt Nam), rồi sau đó trở lại thêm hai năm,

từ 1973-1975, làm việc ở Phòng Tùy Viên Quân Sự. (DAO)

Khởi thủy, được huấn luyện và dự trù phục vụ như một cố vấn, tôi tham dự khóa huấn luyện căn bản sĩ quan lục quân tại Fort Benning, Georgia, tình báo chiến thuật và chuyên biệt về Ðông Nam Á ở Ft. Holabird, Maryland, và học trường Việt ngữ tại Ft. Bliss, Texas. Tới Việt Nam thì được biết những nhiệm vụ cố vấn đang được giảm dần để đi đến chỗ bỏ hẳn; nên thay vào đó tôi được chỉ định vào MACV J-2 với cương vị một chuyên viên phân tích tình báo, trước hết phụ trách Cambodia, rồi tập trung vào Quân Khu IV, bao quát toàn vùng đồng bằng sông Cửu Long. Công việc này mở rộng một cách không chính thức để bao gồm công tác liên lạc giữa Bộ Tổng Tham Mưu Quân Lực Việt Nam Cộng Hòa, các toán cố vấn Mỹ, các chính quyền tỉnh thị của Việt Nam, và cả các đơn vị Quân Lực Việt Nam Cộng Hòa ở vùng IV. Trong 3 năm đó tôi có mặt lúc chỗ này, lúc chỗ khác, trên khắp 18 trong số 44 tỉnh của Việt Nam Cộng Hòa, liên lạc không những với các đơn vị Mỹ và Việt Nam Cộng Hòa mà cả với người Úc, cơ quan viện trợ Mỹ USAID, và CIA. Khi thì đứng vào vị trí rất cao cấp trong những buổi thuyết trình ở tổng hành dinh của MACV cũng như ở Bộ Tổng Tham Mưu Quân Lực Việt Nam Cộng Hòa, tuần lễ sau đó tôi có thể đã lội trên những ruộng lúa tỉnh Kiến Phong cùng với các binh sĩ Ðịa Phương Quân, hay bay ngang tỉnh Ðịnh Tường trên một chiếc trực thăng Huey của Quân Lực Việt Nam Cộng Hòa, hoặc là nằm trong căn cứ Biệt Ðộng Quân Trà Cú bên sông Vàm Cỏ Ðông.

Nói tiếng

Việt là điều vô cùng quan trọng, và trong vòng một tháng sau khi tới Việt Nam,

thật rõ ràng hiển nhiên là những điều tôi từng nghe ở Mỹ, dù là tin tức báo chí

hay là những cuộc thảo luận ngốc nghếch trong các trường đại học, mà có thể

diễn tả được những gì tôi đang trải qua và gặp phải. Nói vắn tắt, tôi tự hỏi

“Nếu quả thật tất cả những người ở Mỹ đang nói về Việt Nam, thì mình đang ở nơi

nào đây?”

Những

thời khắc ngoài giờ làm việc của tôi được dàn trải trọn vẹn trong một kích

thước thực tế hoàn toàn Việt Nam. Dù là ở Sài Gòn, Cao Lãnh, hay Rạch Giá, tôi

cũng lui tới những cái quán nhỏ, với những bàn cà-phê, mì, cháo… háo hức lắng

nghe người dân, người lính Việt Nam nói chuyện, tôi hỏi han, và học được thật

nhiều, nhiều hơn những gì tôi từng học ở Hoa Kỳ.

Sự học

tập của tôi không dừng lại ở năm 1975. Từ đó đến nay tôi đã đọc hằng feet/khối

những tài liệu giải mật và hằng trăm cuốn sách, kể cả những tác phẩm tiếng

Việt, phỏng vấn đến mức từ kỷ lục này qua kỷ lục nọ với những cựu chiến binh

gốc Ðông Nam Á và gốc Hoa Kỳ, săn tìm trong hằng trăm trang web Việt Nam và

Ðông Nam Á trên Internet. Vẫn còn rất nhiều điều về Việt Nam, Lào, Cambodia và

Thái Lan hơn là những gì công chúng Hoa Kỳ tưởng, và những kết luận do những

người ở các xứ ấy tự trình bày lên thì lại không phù hợp với những gì mà hầu

hết mọi con người (ở Mỹ) tưởng là họ biết.

Quả là có

những vấn đề nghiêm trọng về tham nhũng. Ðúng là có những tấm gương về lãnh đạo

bất xứng. Tuy nhiên, chẳng phải ai nói hay gợi ý gì với tôi, mà chính là ngay

lần đầu tiên đến với Sư Ðoàn 9 Bộ Binh Việt Nam Cộng Hòa, tôi đã phát giác khả

năng dày dạn và đầy chuyên nghiệp trong những hoạt động mà tôi chứng kiến ở một

trung tâm hỏa lực cấp sư đoàn. Cũng chẳng ai nói với tôi là Sư Ðoàn 7 Bộ Binh

Việt Nam Cộng Hòa, đơn vị cứ mãi bị kết tội vì khả năng chiến đấu kém cỏi ở Ấp

Bắc nhiều năm trước, đã biến thái thành một đơn vị có hiệu năng chiến đấu cao

dưới tài lãnh đạo chỉ huy của Tướng Nguyễn Khoa Nam, một con người thanh liêm

không một tì vết, song song với tài năng về chiến thuật, mà đến nay vẫn không

hề được công chúng Hoa Kỳ biết tới, tuy đã được người Việt Nam tôn sùng đúng

mức. Cũng không hề có ai ngụ ý hay nói với tôi rằng có thể là lực lượng Ðịa

Phương Quân tỉnh Hậu Nghĩa, là những dân quân của tỉnh, đã làm mất mặt chẳng

những 1 mà tới 3 trung đoàn chính quy của quân đội miền Bắc trong chiến dịch

tấn công năm 1972 của Hà Nội. Họ đã nhai nát và nhổ ra nguyên cả lực lượng xung

kích của đối phương, một lực lượng có thể đã làm đổi chiều lịch sử vào thời kỳ

đó.

Ðịa Phương Quân không được Pháo Binh và Không Quân sẵn sàng yểm trợ như lực lượng chính quy Việt Nam Cộng Hòa, trong đó kể cả Nhảy Dù, Biệt Ðộng Quân, Thủy Quân Lục Chiến. Quân địa phương chỉ dựa vào kỹ thuật chiến đấu căn bản bộ binh. Nếu quân Bắc Việt đánh thủng được chiến tuyến này thì họ đã lập tức trực tiếp đe dọa Sài Gòn, chỉ cách đó 25 dặm, buộc Sư Ðoàn 21 Bộ Binh Việt Nam Cộng Hòa phải rút khỏi quốc lộ 13, từ đó để cho lực lượng Bắc Việt hướng thẳng vào An Lộc. Và như Tiến Sĩ James H. Willbanks viết trong tác phẩm xuất sắc của ông (về trận An Lộc), Sư Ðoàn 21 tuy không thành công trong việc phá vòng vây An Lộc nhưng cũng đã buộc Bắc Việt phải đưa một sư đoàn đổi hướng khỏi chiến trường An Lộc, nếu không, nơi này có thể đã sụp đổ với những hậu quả khốc liệt.

Nói vắn

tắt, Quân Lực Việt Nam Cộng Hòa, một cách toàn diện, đã có khả năng cao hơn

nhiều so với những gì tôi biết trước khi tôi qua Việt Nam, và càng cao hơn

nhiều so với những gì được chuyển tới cho người dân Mỹ. Ngày trước… và ngày nay

cũng vậy.

***

Trở lại thời kỳ đang thảo luận trong bản thuyết trình này, ai cũng biết Quân Lực Việt Nam Cộng Hòa vướng mắc nhiều vấn đề trầm trọng. Ðiều này là hiển nhiên. Nếu không như vậy thì đã chẳng cần phải yêu cầu những đơn vị chiến đấu của Hoa Kỳ, Úc, Nam Hàn, Thái Lan và New Zealand tới đó.

Tuy nhiên, còn có những chỉ dấu cho thấy lực lượng Việt Nam Cộng Hòa khi được trang bị đúng mức và chỉ huy tốt đẹp thì sẽ có khả năng tới đâu. Năm 1966 một tiểu đoàn Biệt Ðộng Quân Việt Nam Cộng Hòa đã gây thiệt hại nặng và đã “giúp” giảm quân số chỉ còn 1 phần 10 cho một trung đoàn Bắc Việt đông gấp ba lần họ ở Thạch Trụ. Tiểu đoàn này được Tổng Thống Johnson tặng thưởng “Huy chương của tổng thống Hoa Kỳ”. Ðại Úy Bobby Jackson, cố vấn tiểu đoàn này, đã mô tả người đối tác của ông, Ðại Úy Nguyễn Văn Chinh (hay Chính?), như là con người tuyệt nhiên không hề sợ hãi. Tiểu Ðoàn 2 Thủy Quân Lục Chiến, mang huy hiệu Trâu Ðiên, đã từng bắt nạt nhiều đơn vị cộng sản miền Nam và chính quy Bắc Việt, chứng tỏ sự xứng hợp của huy hiệu trâu điên (càng có ý nghĩa đối với những ai đã từng gặp phải một con trâu đang nổi giận (và bị nó ăn hiếp!) Công trạng của họ không hề được tường trình trong giới truyền thông tin tức của Hoa Kỳ, và về sau cũng bị bỏ quên trong cái gọi là “lịch sử”…

Năm 1968,

trong bối cảnh cuộc tổng công kích 68 thất bại của Hà Nội, các nhà hoạch định

chính sách của Hoa Kỳ thấy rõ là kế hoạch Việt Nam hóa phải được tăng tiến,

nhưng nhiều người (Mỹ) lại lầm tưởng đó là ranh giới giữa hai thời kỳ, thời kỳ

Quân Lực Việt Nam Cộng Hòa không chiến đấu, và bây giờ là lúc họ bắt đầu chiến

đấu. Thái độ này đã bỏ quên dữ kiện là mức tử vong vì chiến sự hằng tháng của

Quân Lực Việt Nam Cộng Hòa đã vượt xa mức tổn thất trong toàn cuộc chiến của

tất cả các lực lượng đồng minh cộng lại.

Rốt cuộc

thì Quân Lực Việt Nam Cộng Hòa cũng được cung cấp vũ khí tối tân, thay thế

những trang bị thời Thế Chiến Thứ Hai mà hầu hết quân lực này phải sử dụng

(khoảng đầu năm 1968 chỉ có 5% quân đội Việt Nam Cộng Hòa được trang bị súng

M16), nhìn chung thì thua kém vũ khí của Việt Cộng và bộ đội Bắc Việt. Ðồng

thời, quân số cũng tăng tiến, theo như bảng dưới đây trình bày:

(Bảng ghi

những con số gia tăng quân số của các lực lượng chính quy và Ðịa Phương Quân,

Nghĩa Quân, từ năm 1968 đến năm 1972, cho thấy quân số tổng cộng tăng 28%, từ

820 ngàn lên 1 triệu 48 ngàn quân. Trong đó, Không Quân gia tăng quân số tới

163%, Hải Quân tăng 110%, Lục Quân tăng gần 8% quân số)

Trong

bảng này, nhóm từ Anh ngữ ARVN, tức the Army of Republic of Vietnam, có nghĩa

là Lục Quân Việt Nam, chỉ bao gồm 38% Quân Lực Việt Nam Cộng Hòa (tác giả không

đồng ý dùng nhóm chữ ARVN để chỉ Quân Lực Việt Nam Cộng Hòa, và ông dùng nhóm

chữ RVNAF, Republic of Vietnam’s Armed Forces). Ngoài ra còn những thành phần

khác, gồm Cảnh Sát Dã Chiến, Nhân Dân Tự Vệ, và các toán Xây Dựng Nông Thôn.

Lực lượng

xây dựng nông thôn không được coi là lực lượng chiến đấu, còn lực lượng Nhân

dân tự vệ thường bị chế diễu nhưng (những lực lượng này) cũng là chướng ngại

cho quân Việt cộng và quân đội Bắc Việt (North Vietnam’s Army trong nguyên

bản). Có lần một toán cán bộ xây dựng nông thôn đã đẩy lui cả một tiểu đoàn

Việt cộng ở tỉnh Vĩnh Long. Các toán viên biết gọi pháo binh của tỉnh yểm trợ.

Chuyện này cũng không được biết đến để ghi nhận vào tài liệu.

Thành

phần của lực lượng Nhân dân tự vệ thì quá trẻ, hay quá già, hay vì thương tật

nên không gia nhập quân đội chính quy, chỉ phục vụ như lực lượng phòng vệ làng

ấp chống lại những toán thu thuế, tuyển mộ, hay tuyên truyền của cộng sản địa phương.

Nhưng Nhân dân tự vệ cũng là một yếu tố mà cộng sản địa phương phải đối phó sau

năm 1968. Trước đó không có lực lượng này, Việt cộng ở địa phương tự do đi vào

ấp xã lúc ban đêm. Nhiều lúc Nhân dân tự vệ không có hiệu quả, nhiều khi họ bị

tuyên truyền để đi theo Việt cộng, nhưng có nhiều lúc khác lại có những báo cáo

như sau: (Trích từ các sách vở của các tác giả người Mỹ).

“Hai Việt cộng đang bắt cóc một Nhân dân tự vệ thì một Nhân dân tự vệ khác xuất hiện, bắn chết hai Việt cộng này bằng súng M1 (không ghi rõ garant hay carbine), tịch thu được một súng AK47 và một súng lục 9 ly.”

Và “cả

hai ấp Prey Vang và Tahou đêm nay bị bắn súng nhỏ và B-40. Nhân dân tự vệ địa

phương đẩy lui hai toán trinh sát nhẹ.”

Còn nữa:

Một Nhân dân tự vệ 18 tuổi đã là người bắn cháy chiếc xe tăng đầu tiên trong

rất nhiều xe tăng T 54 của Bắc Việt bị tiêu hủy tại An Lộc trong cuộc bao vây

năm 1972.

Hà Nội

không mấy hài lòng về lực lượng này, theo như tài liệu sau đây:

“Chúng

(QLVNCH) tăng cường các lực lượng bù nhìn, củng cố chính quyền bù nhìn và thiết

lập mạng lưới tiền đồn cùng các tổ chức Nhân dân tự vệ bù nhìn ở nhiều làng xã.

Chúng cung cấp thêm trang bị kỹ thuật và tính lưu động cho lực lượng bù nhìn,

thiết lập những tuyến phòng vệ, và dựng ra cả một hệ thống phòng thủ và đàn áp

mới ở những khu vực đông dân cư. Kết quả là chúng đã gây nhiều khó khăn và tổn

thất cho lực lượng bạn (Việt cộng).”

Sự kiện

này không thể xảy ra trước năm 1968, khi lực lượng Nhân dân tự vệ được thành

lập và trang bị bằng những vũ khí thời thế chiến thứ hai do các lực lượng

QLVNCH chuyển giao lại.

Tương tự

như vậy, lực lượng Nghĩa quân, Ðịa phương quân với sự trợ giúp của các toán cố

vấn Mỹ lưu động, được tuyển mộ thêm từ năm 1968 và trang bị vũ khí tốt hơn,

khởi sự tiến bộ, như cố vấn David Donovan thuộc một toán lưu động chứng kiến

trong một trận tấn công bộ binh năm 1970:

“Chúng

tôi vừa vượt khỏi khu mìn bẫy chính thì bị hỏa lực từ một rặng cây trước mặt

bắn tới. Nước văng tung tóe xung quanh, đạn bay véo véo trên đầu, trong tiếng

súng nhỏ nổ dòn. Binh sĩ bây giờ phản ứng tốt lắm, không giống như trước kia cứ

mỗi khi bị bắn là họ gần như tê liệt. Trung sĩ Abney chỉ huy cánh đuôi của đội

hình hàng dọc, bung qua bên phải, sử dụng như thành phần điều động tấn kích,

trong khi chúng tôi ở phía trước phản ứng lại hỏa lực địch. Khi toán của Abney

tới được chỗ địa thế có che chở thì họ dừng lại và bắt đầu tác xạ. Dưới hỏa lực

bắn che đó chúng tôi tràn tới một vị trí khác. Hai thành phần chúng tôi yểm trợ

nhau như vậy và tiến được tới hàng cây, sẵn sàng xung phong. Ba người trong

toán của tôi bị trúng đạn, không biết nặng nhẹ ra sao nhưng mọi người đều xông

tới. Chúng tôi đã hành động khá hay.”

Kinh

nghiệm của Donovan không phải là độc nhất. Cố vấn John Cook nhắc lại niềm lạc

quan của ông vào năm 1970:

“Chúng

tôi (tức Cook và sĩ quan đối tác phía Việt Nam) đang rất lên tinh thần, cảm

thấy như mình là “kim cương bất hoại”. Tinh thần chiến đấu và hăng hái chủ động

tấn công trong quận hết sức cao, khiến chúng tôi truy kích quân địch một cách

gần như khinh suất, liều lĩnh.”

Những

thành tích như vậy không phải mọi nơi đều có. Có những đơn vị không đáp ứng

được trong thời kỳ thay đổi và vẫn bị lãnh đạo chỉ huy kém cỏi, chẳng thực hiện

một cuộc hành quân lục soát với chiến thuật chủ động tấn công nào. Có khi cố

vấn Hoa Kỳ suýt bị giết hay bị dọa giết bởi những sĩ quan địa phương của Việt

Nam mà họ không hòa thuận được. Nhiều cố vấn Mỹ khác không gặp cảnh ngộ khó

chịu đó, nhưng cũng chẳng có ấn tượng tốt nào về hoạt động của những đon vị mà

họ cố vấn. Dù sao thì những chuyện tích cực và thích thú do cố vấn Mỹ chứng

kiến cũng đầy rẫy, nhưng lại hoàn toàn vắng bóng trong những cuộc thảo luận trên

nước Mỹ hay trong ý tưởng của những người Mỹ bình thường, cũng như trong những gì

được dạy dỗ tại các trường học Hoa Kỳ.

Sự tiến

bộ hay những tấm gương xuất sắc ngay trước mắt không phải chỉ hiển hiện trong

những lực lượng lãnh thổ và những sư đoàn bộ binh VNCH, (là những đơn vị)

thường bị cho là không mấy nổi trội về chiến thuật chủ động tấn công. Cố vấn về

kế hoạch bình định của tỉnh Quảng Trị Richard Stevens, trước đó từng phục vụ

trong Thủy quân lục chiến Mỹ tại Việt Nam, tỏ ra ngạc nhiên trước thành tích

của một đơn vị thuộc sư đoàn 1 bộ binh Việt Nam trong trận tấn công một vị trí

phóng hỏa tiễn của quân Bắc Việt:

“Tôi có

ấn tượng hoàn toàn tốt, và thực sự là kinh ngạc, về cách thức hành quân và sự

táo bạo của họ trong mọi việc… Ðây là cuộc hành quân thứ 13 như vậy do vị tiểu

đoàn trưởng này chỉ huy. Ta đang nói chuyện về những chuyên gia hết sức tinh

thục trong những gì họ làm, những người đã từng thực hiện những công tác sởn

tóc gáy và vẫn tiếp tục thực hiện… Các cố vấn của trung đoàn này luôn luôn nói

với tôi lúc tôi ra đó, rằng ‘anh đang làm việc với những người giỏi nhất. Chúng

ta không có điều gì để mà có thể nói cho những người này làm. Chúng ta (các cố

vấn) chỉ có việc yểm trợ hỏa lực mà thôi. Còn về sự hiểu biết trong hành quân,

thì họ là người dạy chúng ta.’ Chúng tôi có các cố vấn người Úc và người Mỹ, họ

đều nói y như nhau.” (tác giả trích luận án Master năm 1987 của Howard C.H

Feng, đại học Hawaii).

Ở miền

Nam, trong lãnh thổ tỉnh Ðịnh Tường thuộc quân khu IV, sư đoàn 7 bộ binh VNCH

cũng thi hành nhiệm vụ không hề có khuyết điểm, theo lời xác nhận của các cố

vấn và các phi công Mỹ lái trực thăng chuyển quân cho các binh sĩ sư đoàn 7

trong những trận tấn công. Sư đoàn này từng bị mang tiếng là sư đoàn “lùng và

né” (thay vì “lùng và diệt”, search and destroy), có thể vì trận Ấp Bắc hồi

1963, nhưng những ai trực tiếp công tác với họ không thể nói gì hơn là những

lời ca tụng, ngưỡng mộ về sự tinh thông chiến thuật và tinh thần hăng hái xông

xáo. Một cựu cán binh Bắc Việt xác nhận về sự dũng cảm của sư đoàn 7 bộ binh:

“Vùng

giải phóng bị thu hẹp… Tôi mất thêm thời gian di chuyển quanh, cố tránh xa các

cuộc hành quân của quân đội VNCH.

Ở Bến Tre

(tức tỉnh Kiến Hòa) sư đoàn 7 VNCH là lực lượng chính gây nên nhiều khó khăn.

Hầu hết sư đoàn được tuyển mộ ở vùng châu thổ sông Cửu Long nên họ biết rành

hết cả vùng. Họ thông thuộc vùng này cũng như chúng tôi.” (tác giả trích dẫn

David Chenoff và Ðoàn văn Toại, sách Chân dung kẻ địch, Random House ở New York

xuất bản năm 1986).

Tình hình

còn tồi tệ hơn khi các đơn vị quân đội Bắc Việt điền khuyết cho các đơn vị

“Việt cộng”, không hiểu biết chút nào về vùng này và được trang bị kém cho cuộc

chiến kiểu các rặng cây ở phía Bắc vùng châu thổ. Một tù binh cho biết bị bắt

sống không bao lâu sau khi tới, lúc anh ta và những người khác được lệnh phục

kích một cuộc hành quân càn quét của sư đoàn 7 vào ngày hôm sau. Bố trí xong

trước bình minh, đội quân đáng lẽ phục kích người ta thì lại bị tấn công từ

phía sau do thành phần bên sườn của sư đoàn 7, trước khi tới lượt lực lượng

chính. (Tài liệu trích dẫn).

Kết quả

của điều này thêm hiển nhiên trong thời gian giữa 1968 và 1971, thời kỳ mà quân

số lực lượng Hoa Kỳ giảm thiểu hơn một nửa, trong khi những cuộc hành quân tấn

công của Việt cộng và quân Bắc Việt lại bị suy giảm rõ rệt:

(Bảng

thống kê trong bài ở đoạn này cho thấy lực lượng Mỹ ở Việt Nam từ năm 1968 đến

1971 đã giảm 322 ngàn quân, tức 58%, các cuộc tấn công của Việt cộng và quân

Bắc Việt cấp tiểu đoàn trở lên giảm 98%, chỉ còn 2 trận, những cuộc tấn công lẻ

tẻ của phía cộng sản cũng giảm, kể cả những vụ bắt cóc, khủng bố, trong khi số

xã ấp có an ninh tăng 56%, diện tích trồng tỉa lúa tăng 9.8%, thương vong vì

chiến tranh của dân và quân phía VNCH giảm 55%, quân số của Việt cộng, Bắc Việt

trên toàn miền Nam giảm 21%).

Tỉ lệ về

các cuộc tấn công lớn nhỏ của phía cộng sản giảm hơn là tỉ lệ giảm quân số, cho

thấy một sự sa sút toàn diện về khả năng quân sự, dưới tỉ lệ dự đoán là 21%

quân số sụt giảm. Ðiều này xảy ra trong khi quân số tham chiến của Hoa Kỳ giảm

tới 58%. Quân cộng sản Bắc Việt và Việt cộng không những chỉ có mặt ít hơn trên

toàn lãnh thổ, mà còn kém khả năng tung ra những cuộc hành quân tấn kích.

Nhiều con

số thống kê của VNCH không chính xác, nhất là con số xã ấp có an ninh thì lại

còn kém xác thực hơn, nhưng biểu đồ khuynh hướng khá rõ ràng, và không có bằng

chứng dù về thống kê hay tin đồn vặt, mà nêu ra điều gì khác hơn là sự xuống

dốc thẳng đứng trong thời vận của quân Việt cộng và quân đội Bắc Việt trong

khoảng thời gian từ 1968 đến 1971. Trong khi Việt cộng, gọi như vậy để phân

biệt với quân Bắc Việt, không bị tiêu diệt hoàn toàn, và những ổ kháng cự có

ảnh hưởng mạnh do họ kiểm soát vẫn tồn tại ở những tỉnh như Chương Thiện, Ðịnh

Tường, Quảng Nam, Quảng Ngãi, thì Việt cộng ở địa phương cũng không còn là một

lực lượng chiến lược. Nếu không có sự xâm nhập đại quy mô của quân Bắc Việt và

sự cung cấp vũ khí hiện đại, thì chiến tranh đã dần dần tự tàn lụi. Những đơn

vị và khu vực của Việt cộng tồn tại được cũng hoàn toàn không phụ thuộc vào

quân đội Bắc Việt để sống còn. Tác giả “phản chiến” Frances Fitzgerald của cuốn

“Lửa trong hồ” (thật khôi hài, là cuốn sách bị đả kích bởi cả người chỉ đạo về

tư tưởng của Hà Nội, Nguyễn Khắc Viện, lẫn người ủng hộ Mặt trận Giải phóng và

Hà Nội, Ngô Vĩnh Long), nhìn nhận rằng khả năng sinh tồn của cả Việt cộng lẫn

QLVNCH hồi năm 1966 là mỗi bên 50%, nhưng đến 1969 thì cơ hội sống còn của Việt

cộng chỉ còn 10%, trong khi tỉ lệ này phía QLVNCH lên hẳn 90%. Nguyễn Văn

Thành, sau 23 năm theo Việt cộng, hồi chánh năm 1970, cho rằng cứu cánh của Mặt

trận giải phóng là vô vọng. Ông ta nêu ra những cuộc hành quân gia tăng của QLVNCH,

sự phát triển những đơn vị Nghĩa quân xã quận và các chương trình Nhân dân tự vệ,

cùng với kế hoạch cải tổ về ruộng đất của chính phủ VNCH, coi đó là những việc

không thể đối phó được nữa. Stanley Karnow khẳng định thằng thừng trong cuốn

sách được đánh giá cao quá đáng của ông, không cần giải thích nguyên do, rằng

đến năm 1971, thì “riêng phía Việt cộng không phải là đối thủ của quân đội

chính quyền Sài Gòn.”

Don Colin

trải qua nhiều năm ở Việt Nam, được nhiều người biết đến qua lối bày tỏ thô lỗ,

phản bác thô bạo và quá đáng, cộng với lối rủa sả om sòm những gì mà ông ta coi

là tào lao nhảm nhí. Ông này đã phải chịu đựng những khó khăn trở ngại, những

khởi đầu sai lạc cùng những vấn đề tương tự, bị coi như toàn những điềm gở.

Nhưng năm 1971 Don Colin cũng thấy những kết quả tích tụ hiển hiện ở vùng châu

thổ:

“Ba mươi

tháng trước, con số những cấp chỉ huy giỏi ở quân khu IV chỉ đếm được trên một

bàn tay. Ngay cả tư lệnh quân đoàn, một cấp chỉ huy tốt, trong sạch và tương

đối có khả năng, cũng nhút nhát, thiếu óc sáng tạo và không đủ sức kích động

thuộc cấp vào những hoạt động xông xáo và tích cực. Cấp tư lệnh sư đoàn thì

phần lớn thiếu khả năng, hầu hết các tỉnh trưởng cũng kém cỏi và tham nhũng.

Các cấp chỉ huy thuộc quyền của họ thì chẳng những noi gương xấu mà nhiều khi

còn phạm khuyết điểm quá hơn cấp trên nữa. Nhưng nay thì chuẩn mực chung về tài

năng, sự trong sạch và tận tâm đã tăng lên tới mức mà trước kia tôi cho là

không thể tưởng tượng được. Sự thay đổi đặc biệt này khiến tôi thêm lạc quan

tin tưởng ở khả năng tối hậu của chính phủ trong việc kiểm soát được Việt Nam

và thành lập một chính quyền ổn định.”

Rồi tới

cuộc tấn công 1972 của Hà Nội, một cuộc tấn công tốc chiến phối hợp phương tiện

cơ khí kiểu cổ điển (a classical blitzkrieg), với đặc điểm là những vũ khí hạng

nặng và những vũ khí chết người được đưa ra sử dụng như hỏa tiễn tầm nhiệt

phòng không SA-7, hỏa tiễn công phá điều khiển bằng dây AT-3, những đoàn chiến

xa T-54 được yểm trợ bằng mấy trăm khẩu đội hỏa tiễn 122 ly, đại bác 130 ly,

hơn hẳn tất cả mọi thứ từng được Hoa Kỳ cung cấp cho lực lượng pháo binh

QLVNCH. QLVNCH bị đánh tơi bời, có lúc đã gần tới kết cuộc, và sự đổ vỡ hiển

hiện rõ ràng. Nhưng cái quân lực đang nằm đo ván đã đứng dậy ở tiếng đếm thứ 8,

hồi phục sức lực và bẻ gãy cuộc tấn công nặng nề nhất ở Việt Nam, tính tới lúc

đó.

Không ai

khác hơn là học giả hàng đầu của Hoa Kỳ về Việt Nam, Douglas Pike, đã tuyên bố

cuộc xâm lược của Hà Nội thất bại là vì “…Nam Việt Nam chiến đấu hơn hẳn quân

đội xâm lăng đến từ phương Bắc.” Nhiều nhà bình luận, kể cả Tướng Ngô Quang

Trưởng, nói tới không lực Hoa Kỳ như một yếu tố quyết định, thì đó đúng là yếu

tố chính. Nhưng những điều ngụ ý nói là QLVNCH không thể chiến đấu nếu như

không có không lực Mỹ, thì đã thiếu sót hai điều căn bản. Thứ nhất, quân đội Mỹ

cũng chỉ được yểm trợ bằng không lực giống như QLVNCH đã được. Thứ hai, là điểm

người ta ít nhìn ra: Không lực Hoa Kỳ là một yếu tố bổ sung để cân bằng với hai

lực lượng vượt trội của Bắc Việt là thiết giáp và, lợi hại hơn cả, là lực lượng

pháo binh hơn hẳn, hỏa tiễn 122 ly chính xác và đại pháo 130 ly gây tàn phá quy

mô ở tầm tối đa 19 dặm (32 km).

Hoa Kỳ

không cung cấp cho đồng minh của họ, VNCH, những vũ khí lợi hại ngang bằng,

nhất là về pháo binh, như Liên Xô và Trung Cộng cung cấp cho Hà Nội. Hà Nội có

hằng trăm hỏa tiễn 122 và đại pháo 130. QLVNCH không đủ đại bác để phản pháo,

chỉ có 24 khẩu 175 ly, không chính xác bằng, bắn chậm hơn các loại 122 ly và

130 ly. Cả pháo đài kiên cố cũng không chịu nổi đạn 130 ly khoan hầm, nổ chậm.

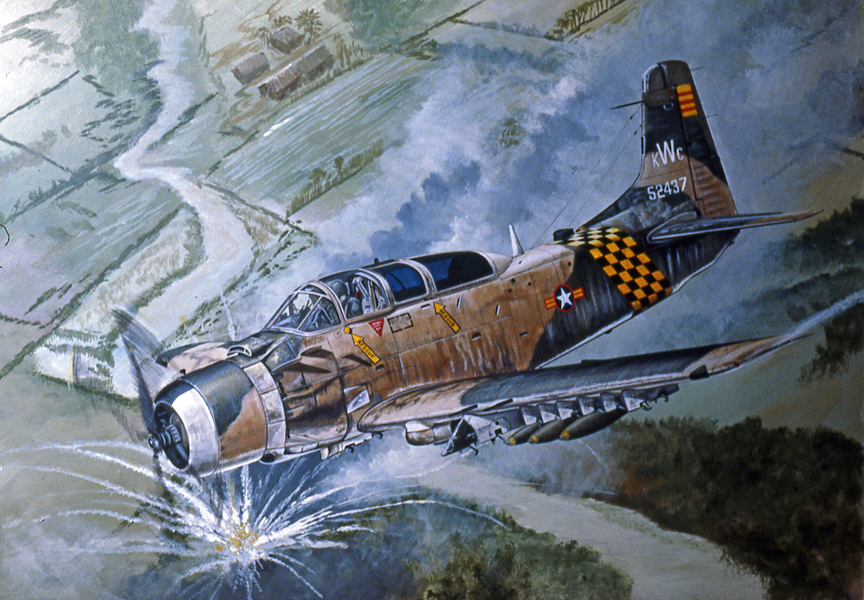

Tựu chung, trở lại đề tài không lực, thì không quân Việt Nam đã thi hành nhiệm

vụ một cách đáng kính phục trong các trận chiến năm 1972, nhưng vẫn bị giới

bình luận Hoa Kỳ hoàn toàn quên lãng. Một chuyên viên điều không tiền tuyến của

Hoa Kỳ tỏ ra ngưỡng mộ một phi công A-37 của Việt Nam mà anh ta cùng thi hành

một vụ tấn công không lục vào vị trí quân Bắc Việt:

“Anh ta

đâm chúc đầu chiếc máy bay xuống tới tầm vũ khí liên thanh, và quả nhiên tôi

thấy nhiều lằn đạn lửa vạch đường sáng bao quanh Pepper dẫn đầu. Tôi la lên báo

động, thì đã thấy anh thả bom ở độ cực thấp và ghi một bàn tuyệt hảo trúng ngay

bức tường. Trong những lần oanh kích tiếp theo ngay đó, các phi công của không

quân Việt Nam cũng ghi bàn hoàn hảo mỗi lần đâm xuống, cũng là mỗi lần họ bị

đạn phòng không bắn lên xối xả… Hỏa lực từ mặt đất vô cùng mạnh mẽ. Quân Bắc

Việt có vẻ như biết rằng đối thủ của họ là người Nam Việt Nam.

“Tôi tin

chắc là hai chiếc A-37 sẽ bị bắn rơi, nhưng cả hai đều xả hết bom đạn của họ

trúng đích, không hề hấn gì. Hai phi công không quân Việt Nam đã trình diễn một

màn tuyệt vời, và tôi ngưỡng phục lòng can đảm của họ trên cả sự thông minh.

Trong giây phút đó lòng can đảm ấy đã vượt hẳn sự khôn ngoan trong những tính

toán hơn thiệt về sự an toàn của cá nhân họ.”

Ðây không

phải là một sự kiện riêng lẻ, theo như một quan sát viên không quân của Mỹ

chứng thực:

“Không quân Việt Nam tự chứng tỏ sự trưởng thành trong cuộc tấn kích 1972… Trong trận phòng thủ Kontum KQVN thật cừ khôi, hết sức tuyệt diệu.”

“Không quân Việt Nam tự chứng tỏ sự trưởng thành trong cuộc tấn kích 1972… Trong trận phòng thủ Kontum KQVN thật cừ khôi, hết sức tuyệt diệu.”

QLVNCH

lãnh cú mạnh nhất của Hà Nội năm 1972, mạnh hơn nhiều so với trận Tết Mậu Thân

1968, về khía cạnh quân số và hỏa lực. Ước lượng có khoảng gần 150 ngàn quân

Bắc Việt đã tham chiến trong giai đoạn 1, và thêm 50 ngàn quân khác bổ sung khi

trận chiến tiếp diễn. Mặt khác, trong trận Tết 1968 chỉ có 84 ngàn quân Việt

cộng và Bắc Việt tham chiến, với pháo binh và xe tăng rất hạn chế. (ngoại trừ ở

quân khu I).

QLVNCH

tiếp tục hoạt động tốt đẹp sau khi hiệp định Paris gian lận được ký kết và bị

vi phạm lập tức. Cuối Tháng 11 năm 1973 một lực lượng đặc nhiệm VNCH đã đánh

đuổi sư đoàn 1 Bắc Việt ra khỏi căn cứ Thất Sơn, gây tổn thất nặng tới nỗi sư

đoàn 1 này của Bắc Việt phải giải thể, số quân sống sót phải gia nhập các đơn

vị khác. Ít tháng sau sư đoàn 7 VNCH tung ra cuộc hành quân lớn để quét các đơn

vị Bắc Việt khỏi mặt khu Tri Pháp ở vùng giáp ranh ba tỉnh Ðịnh Tường-Kiến

Tường-Kiến Phong, gây tổn thất nặng cho địch. Tri Pháp chưa bao giờ bị xâm phạm

trong suốt cuộc chiến tranh, có đặc điểm là những vị trí phòng thủ kiên cố;

cuộc thất trận gây hổ thẹn tới mức nhà cầm quyền cộng sản cảnh cáo các cấp là

phải dấu sự thất bại đừng để bộ đội của họ biết, sợ bộ đội xuống tinh thần. Các

phái đoàn Ba Lan và Hungary trong cái Ủy ban liên hiệp quân sự bốn bên bất lực,

chỉ là gián điệp cho cộng sản Hà Nội. Nhưng một trong những báo cáo của họ năm

1973 xác định là không có đơn vị Việt cộng nào ngang sức với QLVNCH, và cả

những đơn vị thiện chiến nhất của Bắc Việt cũng không sánh được với các đon vị

Nhảy Dù và Thủy quân Lục chiến của VNCH.

Tuy nhiên

đến giữa 1974 thì việc Hoa Kỳ cắt giảm viện trợ bắt đầu từ từ siết cổ QLVNCH, và

đạo quân này chỉ còn nước xuống dốc dần dần từ khi ấy. Ðến 1975 cấp số cung ứng

có sẵn (Available Supply Rate- ASR) dành cho đạn đại bác đã giảm nhanh tới mức

không thể chấp nhận, như theo bảng dưới đây, cho mỗi khẩu đội bắn trong một

ngày:

Năm 1972

Năm 1975 Tỉ lệ giảm

Ðạn 105 ly 180 viên 10 viên 94%

Ðạn 155 ly 150 viên 5 viên 97%

Ðạn 175 ly 30 viên 3 viên 90%

Ðạn 105 ly 180 viên 10 viên 94%

Ðạn 155 ly 150 viên 5 viên 97%

Ðạn 175 ly 30 viên 3 viên 90%

Mọi thứ bị cắt đến tận xương, rồi tận tủy. Nhiều binh sĩ bộ binh được cấp số đạn căn bản là 60 viên M16 cho một tuần lễ. Nhiều đơn vị cấm binh sĩ bắn M16 liên thanh, chỉ được bắn phát một. Các đơn vị chạm địch có khi bị giới hạn chỉ còn được bắn yểm trợ hai trái đạn đại bác, ngoại trừ khi bị tràn ngập. Thiếu cơ phận thay thế, xe tăng, tàu giang tuần, máy bay… nằm ụ chờ rỉ sét (“cho mối mọt ăn”). Tệ hơn nữa, binh sĩ QLVNCH và gia đình họ phải chịu thiếu thốn khi nền kinh tế bị lạm phát 50%, và 25% thất nghiệp. Một bản nghiên cứu của cơ quan DAO thực hiện năm 1974 tiết lộ 82% binh sĩ VNCH không có đủ thực phẩm cho nhu cầu của gia đình. Ðói kém và suy dinh dưỡng làm xuống tinh thần cùng khả năng chiến đấu. Tình hình những tháng sau đó càng xuống dốc, và người ta đau lòng chứng kiến một cái chết chắc chắn sẽ đến vì hằng ngàn vết thương. Một năm sau, khi chính phủ Việt Nam cuối cùng sụp đổ, và, theo như những sách gọi là sách sử, thì nhiều người Mỹ ngạc nhiên, tự hỏi tại sao mọi thứ có thể sụp đổ nhanh chóng như vậy. Lẽ ra câu hỏi đáng chú ý hơn phải là tại sao QLVNCH đã có thể chiến đấu dài lâu sau thời gian giữa năm 1974, với sự thiếu thốn về vũ khí, trang bị, đạn dược, nhiên liệu, thuốc men, với những cái bụng lép kẹp, và gia đình cũng đói khát không kém?

Khi bắt

đầu sự đổ vỡ tan hoang, và đám đông hỗn độn theo lệnh ông Thiệu rút khỏi vùng

cao nguyên, thì khủng hoảng và kinh hoàng xảy đến, phần nào tăng thêm vì những

lệnh lạc trái ngược phát xuất từ dinh Tổng Thống. Nhưng trong sự sụp đổ nhục

nhã sau cùng, vẫn có không ít những trận “Alamo” nhỏ của những người lính VNCH

chiến đấu đến phút cuối.

Sư đoàn

18 đứng vững ở Xuân Lộc là một trận anh hùng ca, nhưng sự có mặt và vai trò của

của Lữ Ðoàn 1 Nhảy Dù trong trận này không hề được biết đến. Khi quân khu II đổ

vỡ và kết cuộc đã gần, sư đoàn 7 VNCH vẫn đánh bại một nỗ lực của quân Bắc Việt

muốn cắt quốc lộ 14, con đường quốc lộ duy nhất nối vùng châu thổ Cửu Long vói

Sài Gòn. Vào ngày cuối, gọi là “ngày quốc hận” (tác giả viết bằng tiếng Việt),

một máy bay AC-119 trang bị liên thanh sáu nòng do các Trung Úy Thanh và Trần

Văn Hiền (hay Thành, Hiển?) còn bay quanh Sài Gòn yểm trợ hỏa lực cho những đơn

vị VNCH lâm chiến sau cùng. Hết xăng, hết đạn, họ đáp xuống đổ xăng và lấy thêm

đạn, sĩ quan hành quân biểu họ không cần cất cánh nữa, tất cả đã mất hết rồi.

Nhưng các Trung Úy Thanh và Hiền vẫn vững chí, nhận nhiên liệu và đạn dược, và

được hai chiếc A1H-Skyraider tháp tùng do Thiếu Tá Trương Phụng và Ðại Úy Phúc

lái, họ tiếp tục lại một trận chiến tuyệt vọng. Sau cùng chỉ còn Ðại Úy Phúc

sống sót, oanh kích đến khi hết đạn. Hai Trung Úy Thanh, Hiền và Thiếu Tá

Trương Phùng đều bị SA-7 bắn rơi, tử trận. Họ đã chiến đấu đến mãi tận giây

phút cuối cùng!

Một cách

tổng quát, cứ bị đói như QLVNCH đã bị thì không một quân đội nào có thể chống

lại cuộc tấn công cuồng bạo của quân đội Bắc Việt, với thừa ứ những khẩu pháo,

xe tăng, vũ khí, nhiên liệu, xe tải quân, đạn dược, do khối cộng sản cung cấp.

Trước một đạo quân VNCH bị rút ruột vì cắt viện trợ như vậy, quân đội Bắc Việt

đã phải tung ra tất cả những gì họ có. Chừng 400 ngàn quân cộng sản, gần 90% là

bộ đội miền Bắc, được đưa ra trận để đánh bại QLVNCH. Hà Nội chưa bao giờ từng

tung ra một lực lượng khổng lồ và hiện đại như họ đã ném vào trận chiến năm

1975. Hà Nội chưa từng rút ra tất cả các đơn vị từ Lào, Cambodia. Về lượng,

quân số 400 ngàn là gần gấp 5 số quân Việt cộng và Bắc Việt lâm chiến hồi tết 1968,

trong khi về phẩm, còn có hằng trăm đại bác tầm xa, hằng trăm xe tăng, hằng

ngàn xe tải, và nguyên một kho vũ khí hiện đại, Ðoàn quân viễn chinh năm 1975

có hơn gấp năm lần khả năng chiến đấu của lực lượng cộng sản hồi Tết Mậu Thân

1968.

Xem xét

sự việc từ một khía cạnh khác, có thể phán đoán mà không sợ sai lầm rằng giả sử

quân đội Bắc Việt bị yếu đi vì cắt giảm mức cung ứng như QLVNCH đã gánh chịu,

thì họ không bao giờ có thể tung ra một cuộc tổng công kích sau cùng, mà hẳn đã

yếu kém hơn thế nhiều. Ưu thế hỏa lực quyết định chiến trường, chẳng phải là

điều gì mới lạ trong lịch sử quân sự. Vào lúc cuối, QLVNCH chịu sự tổn thất

khoảng 275 ngàn tử trận, không kể con số bị ám sát, trong một quốc gia mà dân

số trung bình khoảng 17 triệu. Nước Mỹ với dân số 200 triệu, nếu chịu tổn thất

với tỉ lệ tương đương trong cùng khoảng thời gian ấy, con số tử vong sẽ là 3 triệu

200 ngàn, cần dựng thêm 56 bức tường đá đen nữa mới đủ ghi tên tử sĩ. Ðiều này

không lọt qua mắt của một số nhà quan sát. Sir Robert Thompson, tuy biết rõ

những nhược điểm của QLVNCH, cũng kết luận:

“Quân đội

và chính phủ VNCH vượt qua những cuộc khủng hoảng quốc gia và cá nhân mà có thể

đã nghiền nát hầu hết mọi người, và mặc dù mức tổn thất có thể gây kinh ngạc và

làm sụp đổ Hoa Kỳ, VNCH vẫn duy trì được một triệu quân dưới cờ sau hơn 10 năm

chiến tranh. Vương quốc Anh cũng làm được như thế, theo tỉ lệ tương đương,

trong năm 1917, sau ba năm chiến tranh, nhưng không bao giờ làm được nữa. Hoa

Kỳ chưa bao giờ làm được điều này.” (được nhấn mạnh và thêm vào).

Ký giả Peter Kann, sáng suốt hơn rất nhiều so vói những đồng nghiệp, cũng nhập cuộc, sau khi Sài Gòn thất thủ:

Ký giả Peter Kann, sáng suốt hơn rất nhiều so vói những đồng nghiệp, cũng nhập cuộc, sau khi Sài Gòn thất thủ:

“Nam Việt

Nam quả đã phấn đấu để kháng chiến trong nhiều năm ròng rã, không phải lúc nào

cũng được Hoa Kỳ giúp đỡ dồi dào. Ít có quốc gia hay xã hội nào mà tôi cho là

có thể chiến đấu được lâu dài đến thế.”

Kế hoạch

Việt Nam hóa có hiệu quả không? QLVNCH có trưởng thành nên một lực lượng chiến

đấu có khả năng?

Có thể

biện luận rằng kế hoạch Việt Nam Hóa có hiệu quả, nhưng lại bị moi ruột vì cắt

giảm viện trợ chí tử. Năm 1974 có cuộc thăm dò các tướng lãnh Hoa Kỳ từng phục

vụ tại Việt Nam, nhằm tìm hiểu chương trình Việt Nam hóa thành công tới mức

nào. Các câu hỏi và trả lời như sau:

1. QLVNCH

là lực lượng chiến đấu rất đáng chấp nhận?: 8% đồng ý.

2. QLVNCH xứng đáng và cơ may hơn 50% đứng vững trong tương lai?: 57% đồng ý.

3. Có nghi ngờ khả năng QLVNCH có thể đẩy lui một cuộc tấn công mạnh của lực lượng Việt cộng-Bắc Việt trong tương lai?: 25% nghi ngờ.

4. Ý kiến khác và không ý kiến: 10%.

2. QLVNCH xứng đáng và cơ may hơn 50% đứng vững trong tương lai?: 57% đồng ý.

3. Có nghi ngờ khả năng QLVNCH có thể đẩy lui một cuộc tấn công mạnh của lực lượng Việt cộng-Bắc Việt trong tương lai?: 25% nghi ngờ.

4. Ý kiến khác và không ý kiến: 10%.

Như vậy 65% các tướng lãnh chỉ huy của Hoa Kỳ dành cho QLVNCH tỉ lệ phiếu thuận, tuy nhiên những câu trả lời này có thể đã mang khuynh hướng lệch theo chiều xuống. Không biết bao nhiêu vị tướng phục vụ trong khoảng 1966-1967, trước khi QLVNCH thực hiện những đổi thay to lớn nhất. Chức vụ mà các sĩ quan này đảm trách là gì, họ làm việc với ai, và họ quen thuộc với quân đội VNCH ở mức độ nào, sự tăng tiến hiệu năng của lực lượng Ðịa phương quân, Nghĩa quân, vân vân… cũng không được tiết lộ. Câu hỏi cũng không hỏi: “Nếu quân đội Mỹ cũng bị cắt giảm cung ứng như QLVNCH vào năm 1974-1975 thì còn đứng vững được bao lâu?”

Ðiều có

thể nói chắc chắn, là QLVNCH từ 1968 trở đi đã hoàn thành nhiệm vụ tốt đẹp hơn

nhiều so với những gì được biết đến một cách chung chung, rằng các đơn vị QLNCH

đã thi triển tài năng để có thể đứng vững và đánh bại quân xâm lược Bắc Việt

trong năm 1972, thường là không cần tới sự yểm trợ hỏa lực ồ ạt của pháo binh

và không quân chiến thuật, như trong trường hợp của Nghĩa quân và Ðịa phương

quân. Ðiều có thể nói chắc chắn nữa là sự hiểu biết của người Mỹ về việc này

thấp kém đến kinh tởm, thấp tít mù xa như vực thẳm không đáy.

Một yếu

tố rất quan trọng nữa mà nhiều nhà bình luận bỏ qua và tới nay vẫn không biết

gì hơn, là thế hệ các sĩ quan, hạ sĩ quan QLVNCH trẻ trung hơn, hết lòng hết dạ

vì mục tiêu một nước Việt Nam không cộng sản. Họ cởi mở, ngay thật, biết lẽ

phải, trong sạch, biết nhìn nhận phải trái, ví dụ như họ cho là người Thượng

không nên được đối xử thấp kém hơn, rằng tham nhũng cần bị công kích, rằng một

quốc gia Việt Nam mới cần được tạo thành, bung ra khỏi mọi xích xiềng quá khứ.

Nhiều người trong số này có thể có vị trí tốt để tránh quân dịch hay giữ một

chỗ an toàn, không ra trận; nhưng họ không cần cả hai thứ đó, đã có mặt trong hàng

ngũ phục vụ tại những vị trí chiến đấu đầy nguy hiểm, với tư cách những người

tình nguyện. Thái độ của họ được một sĩ quan trẻ của QLVNCH bày tỏ:

“Những

người ở cỡ tuổi tôi vào quân đội vì chúng tôi có một lý tưởng, chúng tôi hiểu

được cuộc sống trong một thế giới tự do ra sao, và sống trong thế giới cộng sản

ra sao. Không phải như người ta nói, rằng những ai vào quân đội thì chỉ vì đến

tuổi lính và không có lý tưởng gì riêng cho mình. Nhưng người Mỹ không bao giờ

có vẻ hiểu ra điều đó.”

Trần Quốc

Bửu là chủ tịch Liên Ðoàn Lao công Nam Việt Nam, tương đương với AFL-CIO của

Hoa Kỳ. Ông có ảnh hưởng và có thể xếp đặt cho con trai ông tìm một chỗ an

toàn, an toàn hơn nhiều so với vị trí của anh này là một sĩ quan bộ binh VNCH.

Trong những tuần lễ sau cuối của VNCH, lúc bị Bắc Việt dập pháo tơi bời, tuyệt

vọng trong cảnh thiếu đạn, con ông Bửu viết cho ông một lá thư:

“Ba phải

giải thích cho người Mỹ hiểu sự nghiêm trọng của tình hình chúng ta… Họ phải

cung cấp viện trợ quân sự và kỹ thuật như họ đã hứa. Con xin ba, ba à, hãy can

thiệp với họ. Nếu không, chúng ta sẽ bị đè bẹp và thất trận. Tụi con không hèn

nhát. Tụi con không sợ chết… Trong mọi tình huống, con sẽ giữ vững vị trí và

không rút lui.”

Con ông

Bửu hy sinh tại chiến trường.

Bác sĩ

Phan Quang Ðán là quốc vụ khanh về định cư và tị nạn, một cựu đối lập với ông

Ngô Ðình Diệm, nổi tiếng nhờ trong sạch. Ông có đủ quyền lực và ảnh hưởng để

giữ con trai là Phan Quang Tuấn khỏi bị nguy hiểm. Cả hai cha con đều không

chọn điều đó, và Tuấn tình nguyện lái A-1E Skyraider, chỉ dùng để yểm trợ chiến

thuật gần cho các dơn vị dưới đất. Sau khi tiêu diệt 7 xe tăng quân Bắc Việt

tại khu vực ngưng chiến, trong trận tấn công 1972 của Hà Nội, Ðại Úy Tuấn bị

hỏa lực phòng không địch bắn rơi, tử trận. Những cá nhân ấy không phải là duy

nhất. Người viết bài này hằng ngày gặp những phi công trực thăng võ trang trẻ

tuổi, những sĩ quan trẻ trong Biệt động quân, Thủy quân lục chiến, Nhảy dù, tất

cả đều tình nguyện lãnh nhiệm vụ tác chiến nguy hiểm, bị “lưỡng đầu thọ địch”,

với hệ tư tưởng về một nước Việt Nam cộng sản, và với nạn tham nhũng trở thành

thông lệ hằng ngày ở Sài Gòn. Một trong những tấm gương gây xúc động hơn nữa về

lòng tận tụy với chính nghĩa quốc gia, là cảnh các sinh viên sĩ quan trường Võ

Bị quốc gia Ðà Lạt chuẩn bị cho trận đánh sau cùng của họ, mà ký giả Pháp Raoul

Coutard chứng kiến, vào lúc họ tiến ra để chặn các đơn vị quân đội Bắc Việt

đang tiến tới:

“- Anh

sắp bị giết đó!

- Vâng. Một sinh viên sĩ quan trả lời.

- Sao vậy? Ðã kết thúc rồi mà!

- Tại vì chúng tôi không ưa cộng sản.

Và, lòng đầy can đảm, những sinh viên trẻ tuổi trong bộ quân phục mới toanh, tuyệt đẹp, giày bóng loáng, tiến ra để chờ chết.”

- Vâng. Một sinh viên sĩ quan trả lời.

- Sao vậy? Ðã kết thúc rồi mà!

- Tại vì chúng tôi không ưa cộng sản.

Và, lòng đầy can đảm, những sinh viên trẻ tuổi trong bộ quân phục mới toanh, tuyệt đẹp, giày bóng loáng, tiến ra để chờ chết.”

Trường

Thiếu Sinh quân ở Vũng Tàu, là trường nội trú, trong học trình có dạy quân sự

cho các thiếu niên Việt Nam có cha tử trận. Khi đến lúc cuối, những em trai

12-13 tuổi đuổi các em thiếu sinh quân nhỏ hơn về nhà, lập chướng ngại vật bảo

vệ trường và đối đầu với các đơn vị quân Bắc Việt:

“Họ tiếp tục chiến đấu sau khi tất cả mọi người khác đã đầu hàng!… Nhiều người trong số họ bị giết. Và khi quân cộng sản tiến vào, các thiếu sinh quân đánh trả. Cộng sản không vào được ngôi trường ngay lúc đó.”

“Họ tiếp tục chiến đấu sau khi tất cả mọi người khác đã đầu hàng!… Nhiều người trong số họ bị giết. Và khi quân cộng sản tiến vào, các thiếu sinh quân đánh trả. Cộng sản không vào được ngôi trường ngay lúc đó.”

Những con

người tương tự (lúc đó) đang gia tăng trong mọi cấp bực của QLVNCH, và nhu cầu

cấp bách của tình hình buộc sự thăng thưởng phải dựa trên khả năng, không dựa

trên quan hệ chính trị hay quan hệ gia đình.

Giới

truyền thông Hoa Kỳ đã thất bại tại Việt Nam, thua bại hoàn toàn và thê thảm

hơn nhiều so với các lực lượng quân sự của VNCH, Hoa Kỳ và các đồng minh. Họ

thường lên án bằng những lối can thiệp đầy tự phụ và tự mãn. Một cuộc thăm dò

9,604 chương trình truyền hình của NBC, CBS và ABC từ 1963 đến 1977 cho thấy rõ

những sự thiếu sót của những cái gọi là bài tường thuật truyền hình. 0.7%

chương trình nói về việc huấn luyện QLVNCH. 0.8% về bình định. 2.7% về chính

quyền hay quân lực VNCH hay Cambodia. Tổng cộng chỉ có 392 chương trình, tức

2.7% toàn bộ các chương trình tin tức truyền hình Mỹ, tường trình về Việt Nam.

Không có một lời nào về hơn 200 ngàn hồi chánh viên, không một lời về QLVNCH

thiện chiến. Không có gì về những phi công Ong Chúa lừng danh của trực thăng Việt

Nam cứu mạng cho những toán lực lượng đặc biệt Hoa Kỳ chạm địch dọc đường mòn

Hồ Chí Minh. Hầu hết người Mỹ, nếu không phải là tất cả, đều nhớ hình ảnh bi

hùng của một người Trung Hoa đứng trước đoàn xe tăng ở quảng trường Thiên An

Môn, nhưng không ai biết Trung Sĩ thủy quân lục chiến Việt Nam Huỳnh Văn Lượm

đứng trên cầu Ðông Hà chặn đứng đoàn xe tăng Bắc Việt, tác xạ bằng khẩu súng

chống tăng LAW của anh:

“Cảnh

tượng anh lính TQLC nặng có 95 cân Anh trụ ngay trên đường tiến của 40 xe tăng

không có ý nào muốn dừng lại, trên một khía cạnh thì là dại dột một cách khó

tin. Trên khía cạnh khác, quan trọng hơn, hình ảnh này mang đầy niềm phấn khích

đối với một lực lượng phòng thủ mỏng manh đến thê thảm, và với nhiều người tị

nạn, ít ai trong số đó từng chứng kiến một hành động thách đố dũng cảm đến thế…

Sự anh dũng lạ thường của người lính thủy quân lục chiến Nam Việt Nam này đã

khiến đợt tấn công bằng xe tăng, tới lúc đó chừng như chắc chắn phải thắng lợi,

đã bị mất đà tấn kích.”

Trong một

khoảnh khắc mà giới truyền thông mang tật cận thị lên tiếng, thì phóng viên

Donald Kirk tuyệt đối không tỏ ra sự quan tâm nào khi đến thăm sư đoàn 7 bộ

binh VNCH, nơi đã trở nên một đơn vị có hiệu năng cao tuyệt dưới tài lãnh đạo

của Tướng Nguyễn Khoa Nam. Quân nhân trong sư đoàn nhận thức rõ giá trị những

nông trại của sư đoàn do tướng Nam thiết lập để giảm bớt gánh nặng kinh tế cho

binh sĩ của sư đoàn 7. Nhưng khi Kirk và các phóng viên khác bị giữ lại ở một

điểm chắn đường của quân đội Bắc Việt rồi được thả ra sau đó, thì Kirk lại thất

vọng vì anh ta không có cơ hội để nói chuyện với bộ đội Bắc Việt:

“Tôi cứ

nghĩ mãi về việc trông họ như vừa bước ra khỏi cuốn phim… Họ có vẻ là những tay

chính quy, vậy đó. Tôi chỉ mong sao chúng tôi đã có thể ở lại thêm và nói

chuyện với họ lâu hơn.”

Ông Kirk

có thể yên tâm rằng quân sĩ sư đoàn 7 đều là “những tay chính quy”, rất đáng để

nói chuyện, và học hỏi nơi họ. Anh chàng này, cũng như đông đảo trong giới

truyền thông làm tin tức, đã không để ý gì đến việc đó, cho nên không có gì kỳ

bí về nguyên nhân vì sao hầu hết những người Mỹ từng phục vụ tại Ðông Nam Á đều

nhìn cái giới truyền thông tin tức này với sự khinh miệt gay gắt.

Quân đội Đồng Minh tham chiến tại Việt Nam

Phải chi giới này chịu khó quan hệ với quân dân Việt Nam mà họ gặp gỡ, như tôi đã làm nhiều lần, thì đám ký giả hẳn đã biết trong mắt những người Việt ấy chủ nghĩa cộng sản của Hà Nội là điều đáng khinh bỉ và kinh tởm, như một loại phản bội văn hóa và truyền thống Việt Nam. Không phải những người Việt này chiến đấu và hy sinh để bảo vệ “chế độ tham nhũng của Thiệu”, mà là để gìn giữ một cuộc sống tốt đẹp hơn cho người dân, cho con cái, và cho đất nước của họ. Một thủy quân lục chiến Việt Nam diễn giải và lột tả chân xác nhất về điều này, khi anh ta nói với tôi rằng sau khi quân đội VNCH giải quyết xong với quân đội miền Bắc, họ sẽ quay súng lại chống đám tham nhũng ở Sài Gòn. Những sự kiện thảm thiết bi thương sau năm 1975 đã chứng thực tính thuận lý và giá trị của điều quyết tâm ấy.

Giới

truyền thông giải trí và giới giáo dục ở Hoa Kỳ cũng chẳng khá gì hơn, mà còn

mãn nguyện khi lặp lại, nếu không phải là thêm mắm thêm muối vào cái chuyện

thần thoại do truyền thông dựng lên. Một cuốn sách sử trung học được sử dụng

rộng rãi ở Mỹ có chương sử về Việt Nam không hề nói đến Quân Lực Việt Nam Cộng

Hòa, chỉ viết rằng: “Việt Nam hóa thất bại,” ngoài ra còn gom góp hơn 200 điều

khẳng định có thể được chứng minh là sai trái và mang hoàn toàn tính chất dẫn

dắt lạc hướng, trong 13 trang bài học. Có nói đến vụ tấn công sang Cambodia,

nhưng không nói gì về việc quân Việt Nam Cộng Hòa tham dự đông đảo hơn lực

lượng Hoa Kỳ, 29 ngàn quân so với 19,300 quân Mỹ tham chiến. Sách cũng không

nói lên rằng trước khi chính thức mở chiến dịch, quân đội Việt Nam Cộng Hòa đã tấn

công trước vào các vị trí phòng thủ của quân đội Bắc Việt ở Cambodia. Quân Lực

Việt Nam Cộng Hòa đã hoàn toàn vô hình, như một đề tài sẽ được trình bày nơi

đây (trong cuộc hội thảo).

Phim ảnh và truyền hình lại càng tệ hơn, mặc dù có được một số phim tài liệu lịch sử. Cả cuốn phim “Bat 21”, nhằm miêu tả cuộc tìm cứu trung tá Iceal Hambleton năm 1972, không thể hiểu được tại sao đã loại hẳn sự kiện là một chiến sĩ Người Nhái Việt Nam, Nguyễn Văn Kiệt, người cùng thi hành công tác tìm cứu đó với người nhái Hoa Kỳ Tom Norris, được tặng thưởng huy chương US Navy Cross do sự dũng cảm và anh hùng của Kiệt. Làm sao công chúng có thể trông mong được biết bất kỳ điều gì khi mà chế độ “kiểm duyệt” trên thực tế đã bôi xóa tất cả và từng dấu vết của sự hoạt động gương mẫu của Quân Lực Việt Nam Cộng Hòa?

***

Sau cùng, cần phải nhìn nhận rằng Quân Lực Việt Nam Cộng Hòa đã bị đè bẹp bởi một gánh nặng trầm kha không thể nào vượt thắng: đó là một đồng minh bất xứng, ngu dốt và gây rối một cách đáng kinh ngạc, dưới hình thức cái chính phủ Hoa Kỳ.

Một hội

nghị chuyên đề toàn diện nên được tổ chức về đề tài này, và cần phải có hội

nghị đó. Những chiến lược giả hiệu phát xuất từ Washington, về bản chất, phải

bị coi là cẩu thả mang tính cách tội ác. Không một hành động nào được tung ra

để chặn và giữ đường mòn Hồ Chí Minh. Không có con đường này thì cuộc chiến

tranh của Hà Nội đã không thể nào tiến hành được. Không một việc gì được thi

hành để giao chiến với chiến tranh thông tin tuyên truyền-phản tuyên truyền

dưới hình thức gọi là địch vận, một trong những chiến lược quan trọng của Hà

Nội, được thi hành với những sự lừa gạt quỷ quyệt xuất chúng. Không làm một

việc gì mãi đến khi cơ quan CORDS được thành lập để ra kế hoạch và phối hợp những

hoạt động quân sự và bình định về mặt tình báo. Không làm một việc gì để khai

triển một liên minh rộng lớn như một chiến trường chung của người Việt, người

Lào, người Cambodia và Thái Lan, chống lại kẻ thù chung, trong khi Hà Nội đã

làm y như vậy: thiết lập một cấu trúc chỉ huy chiến trường Ðông Dương nhằm kết

hợp mọi yếu tố vào một chiến lược gắn bó cho toàn khu vực. Lý cớ về lãnh đạo

của Hoa Kỳ là mù lòa, lần mò vụng dại như con heo trên tảng băng, như một con

cóc vàng, rất giàu có nhưng cũng rất ngu độn. (Những chữ in đậm là những chữ

tác giả viết bằng tiếng Việt)

Những kế hoạch, những đề nghị đi ngược dòng lịch sử khó có thể được chứng minh hoàn toàn chắc chắn, và có thể chiến tranh (Việt Nam đã qua) là một cuôc chiến không thể nào thắng được.

Có thể

như vậy. Tuy nhiên những người Mỹ, người Úc đã phục vụ sát cánh những chiến hữu

của họ trong Quân Lực Việt Nam Cộng Hòa, “những chiến hữu, bạn bè, giống như

anh em ruột,” (viết tiếng Việt trong nguyên bản) mang trong lòng họ nỗi buồn

sâu xa vì đã thua cuộc, hay đã mất biết bao bạn bè tận tụy, mất cả niềm vinh dự

lớn lao cho việc đã cố gắng đạt cho kỳ được một thế giới tốt đẹp hơn cho những

người dân thường của Việt Nam, Lào, Cambodia và Thái Lan. Họ không bị thúc đẩy

vì những quan niệm tinh vi về địa lý chính trị thế giới, nhưng đúng hơn, là do

sự kính trọng và ngưỡng mộ đối với nhiều người Ðông Nam Á đã biết yêu quý xứ

sở, những con người đã “thề bảo vệ giang sơn quê hương”.

Nhiều trang lịch sử còn chưa được lật ra, phản ảnh sự tiếp nối cái khuynh hướng của Hoa Kỳ chỉ toàn nhìn qua con mắt người Mỹ, bị lọc qua định kiến của người Mỹ. Một số sách vở nói đến Việt Nam như một “giai đoạn thử thách đầy khổ đau của Hoa Kỳ,” mà chưa từng một lần hỏi xem người Ðông Nam Á đã trải qua loại thử thách khổ đau nào. Ðầy dẫy những dữ kiện lịch sử quý giá và những nét quan sát sắc sảo nằm trong những cuốn sách được viết do người Việt Nam (và cả người Lào). Thiếu những sách đó, không thể nào có được sự hiểu biết toàn diện. Những tác phẩm của Lý Tòng Bá, Hà Mai Việt, Phạm Huấn, Phan Nhật Nam, Trần Văn Nhựt, và nhiều người khác, đang kêu gào đòi được dịch thuật, cũng như hằng chục bài phổ biến hằng năm trên sách báo tạp chí quân sự và các ấn bản khác. Nhiều bài trong đó mô tả những trận đánh, những diễn tiến và những nhân cách, không hề được các sử gia Hoa Kỳ biết đến. Không tham khảo những nguồn đó thì chắc chắn là chiến tranh Việt Nam, cũng là Chiến Tranh Ðông Dương của Hà Nội, sẽ mãi là những bí ẩn không thể giải đoán, và lịch sử chân thực của Quân Lực Việt Nam Cộng Hòa sẽ mãi bị chôn vùi dưới tầng lớp này qua tầng lớp nọ của những chuyện hoang đường, của sự không thông hiểu, và của sự giả định vô căn cứ.

Nhà sử học Bill Laurie

Dịch giả: Nguyễn Tiến Việt

Dịch giả: Nguyễn Tiến Việt

Nguồn:

Bill Laurie is not only a Vietnam

Vet, but a Vietnam War historian as well (a true expert on Vietnam War,

not the kind of "military pundits" who used to talk "bullshit" in some

military programs on TV). His following writing has been presented at

The Vietnam Center Conference (Texas, March 29. '06) on the the subject

"ARVN: Reflections and Reassessments After 30 Years." Don't let the

quotations, statistic tables, and references intimidate you, this ARVN

report speaks outright simple and is worth reading.

|  |  |  |  |

|  |  |  |  |

|  |  |  |  |

|  |  |  |  |

|  |

ARVN: 1968 – 1975

ARVN: 1968 – 1975

by Bill Laurie

1 RVNAF,

the Republic of Viet Nam Armed Forces, underwent a significant change,

both qualitatively and quantitatively, between 1968 and 1975. It was a

change that went unnoticed by the news media and remains generally

unknown to the American public, and is inadequately identified and

described in many would-be "history"books, in part because the nature

and extent of change could not readily be foreseen or predicted based on

RVNAF performance and capabilities up to 1968. None of this is to deny

serious problems existed, or that corruption and poor leadership did not

continue to plague RVNAF's ability to defend the Republic of Viet Nam,

yet to a degree these problems were being addressed and the

positive aspects of RVNAF cannot be excluded from honest history.

1 RVNAF,

the Republic of Viet Nam Armed Forces, underwent a significant change,

both qualitatively and quantitatively, between 1968 and 1975. It was a

change that went unnoticed by the news media and remains generally

unknown to the American public, and is inadequately identified and

described in many would-be "history"books, in part because the nature

and extent of change could not readily be foreseen or predicted based on

RVNAF performance and capabilities up to 1968. None of this is to deny

serious problems existed, or that corruption and poor leadership did not

continue to plague RVNAF's ability to defend the Republic of Viet Nam,

yet to a degree these problems were being addressed and the

positive aspects of RVNAF cannot be excluded from honest history. I experienced this personally, arriving in Viet Nam in late 1971, serving one year with MACV, and returning for two more years, 1973-1975, with the Defense Attache Office. Originally scheduled and trained to serve as an advisor, I attended Infantry Officer Basic at Ft. Benning, Georgia; Combat Tactical Intelligence and Southeast Asia Orientation at Ft. Holabird, Maryland; and Viet Namese Language School at Ft. Bliss, Texas. Upon arriving in Viet Nam I was told advisory slots were being phased out and instead I was assigned to MACV J-2 as an intelligence analyst, first covering Cambodia and then concentrating on Military Region IV, covering the entire Mekong Delta. This job expanded informally and encompassed liaison work with RVNAF staff, US advisory teams, GVN provinces, and RVNAF units in the Delta. During these three years I was, at one time or another, in 18 of the former RVN's 44 provinces, dealing with not only US and RVNAF elements but also with the Australians, USAID, and the CIA. I sat in on very high level briefings at MACV HQ as well as the RVN JGS, while the next week I might be in a Kien Phong rice paddy with PF troops, or flying across Dinh Tuong province in an ARVN Huey, or at Tra Cu Ranger Base along the Vam Co Dong River. Of great importance was the ability to speak Viet Namese, and within one month after arriving in Viet Nam it was clearly apparent that nothing I'd heard in the US, either the "news reports"or rather silly debates on college campuses, described what I experienced and encountered. In sum, I asked myself "If all those people in the

2 U.S. are talking about Viet Nam, then where am I?" My off-duty hours were spent entirely within a Viet Namese dimension of reality. Whether in Saigon, or Cao Lanh, or Rach Gia, I frequented the "quan nho,"the card-table soup and coffee stands, eagerly listening to Viet Namese people and troops, asking questions, and learning far, far more than I'd ever learned in the States, or even knew there was to be learned. My education did not end in 1975. Since then I have read cubic feet of declassified documents and hundreds of books (to include works in Viet Namese), interviewed scores upon scores of Southeast Asia- and US-born veterans of the war, and prowled the internet's hundreds of Viet Nam and Southeast Asia websites. There remains much, much more to Viet Nam, Laos, Cambodia and Thailand than is suspected by the American public, and conclusions presenting themselves do not conform to what most people think they know.

Yes, there were serious problems with corruption. Yes, there were examples of inept leadership. Still, no one told me, or even suggested, that my initial exposure to the ARVN 9th Infantry Division would reveal the professional and highly competent performance witnessed at a division FDC (Fire Direction Center for allocation of supporting artillery fire). Nor had anyone told me that the 7th ARVN Infantry Division, forever condemned by its lackluster performance at Ap Bac, years earlier, had evolved into a highly effective unit under the leadership of General Nguyen Khoa Nam, a man of impeccable integrity and tactical skills who remains unknown to the American public, while being justly revered by the Viet Namese people. Nor did any suggest it would even be possible for Hau Nghia Province's RF forces, the provincial militia, to thoroughly humiliate not one but three NVA regular regiments during Hanoi's 1972 Offensive, systematically chewing up and spitting out attacking enemy forces that could have feasibly changed the course of history during this period.1 The RF did not have the artillery and air support available to regular ARVN (to include Airborne and Rangers) and Marine units, and relied heavily on basic hard-ball infantry skills. Had the NVA broken through they would have posed an immediate and direct threat to Saigon, a mere 25 miles away, forcing ARVN 21st Division forces to pull back from QL 13, and thereby allow NVA forces to direct all their attention to An Loc. As has been noted by James H.

3 Willbanks(2) in his excellent work, the 21st division, while not succeeding in breaking through to besieged An Loc, did force the NVA to divert a division away from An Loc, which conceivably might otherwise have fallen, with dire consequences.

In sum, RVNAF in its entirety, and often mistakenly referred to as simply "ARVN,"was capable of far more than I had learned before going to Viet Nam, and far more than was conveyed to the American people. Then...and now. Going back to the period discussed in this presentation, it is acknowledged that RVNAF had serious problems. This is obvious. Were this not so, U.S., Australian, South Korean, Thai and New Zealand combat units would not have been required. Still, there were indications of what well-led, properly armed and equipped RVNAF forces were capable of. In 1966 the 37th ARVN Ranger battalion decimated an NVA regiment three times its size at Thach Tru, receiving a Presidential Unit Citation from Lyndon Johnson for its feat. An American advisor to the 37th, Capt. Bobby Jackson, described his counterpart, company commander Capt. Nguyen Van Chinh, as being "utterly fearless."3 The 2nd Marine, or Thuy Quan Luc Chien, Battalion, whose shoulder patch depicted a "Trau Dien,"a "Crazy Buffalo,"had likewise bullied VC and NVA units, demonstrating the appropriateness of their unit symbol (all the more meaningful for those who've encountered an enraged water buffalo). Their accomplishments were unreported in the US news media and are ignored in later day "histories."

By 1968, and in the aftermath of Hanoi's failed '68 strategic counter- offensive, it was clear to US decision makers that "Viet Namization"must be accelerated, which many people falsely assume is the demarcation between a period when RVNAF wasn't fighting, and now would begin to fight. This overlooks the fact that RVNAF monthly combat fatalities greatly exceeded those of combined allied forces for the entire war. RVNAF was finally supplied with modern weapons, replacing the WW II equipment most had been using (by early 1968 only 5% of RVNAF were using the M-16 rifle), generally inferior to VC/NVA weaponry. Concurrently, RVNAF strength increased the board:

4 1968 1972

Regular Forces

Army 380,000 410,000 Plus 30,000/7.9%

Air Force 19,000 50,000 Plus 31,000/163%

Navy 19,000 42,000 Plus 23,000/110%

Marines 9,000 14,000 Plus 5,000/56%

Total Regular 427,000 516,000 Plus 89,000/21%

RF/PF Militia*

RF 220,000 284,000 Plus 64,000/29%

PF 173,000 248,000 Plus75,000/43%

Total 393,000 532,000 Plus 139,000/35%

Overall Total 820,000 1,048,000 Plus 228,000/28%

(4)

*The term "militia"is often used yet may wrongly suggest the final evolution of these elements took the form of part-time irregulars. Sometimes referred to as "territorials,"the RF(Regional Forces, or Dia Phuong Quan) and PF(Popular Forces, or Nghia Quan) were full time military units, typically limited to their home province, or district, respectively.

As can be seen, "ARVN"-the Republic of Viet Nam ARMY, was only one component-56%-of the total armed forces. There were yet other elements, to include the National Field Force Police, People's Self Defense Force/Nhan Dan Tu Ve (PSDF), and Rural Developemt (RD) teams. While the latter were not considered full-time combat troops, and the PSDF often ridiculed, they were an impediment to the VC/NVA. In one case, not known to be documented, an RD cadre team turned back a VC battalion in Vinh Long province, its members skilled in calling in province artillery.5 While the PSDF were too young, too old, or too disabled to join the regular military, serving only as a village hamlet defense force against local VC tax, recruiting, or agitprop teams, they were another factor the local communists had to deal with, and one that had not been in place before 1968, when local VC could freely enter hamlets at night. Sometimes the PSDF were ineffectual, and sometimes they were propagandized into joining the VC (6), yet at other times:

5 "...they (two VC) were trying to abduct a member of the PSDF when another PSDF appeared on the scene and shot both of them dead with an M-1. An AK-47 and 9mm Chicom pistol were captured."

And... "Both Prey Vang and Tahou hamlets received small arms fire and B-40s tonight. The local PSDF managed to drive off two light ground probes."(7)

It was also an 18-year-old PSDF member who knocked out the first of many tanks destroyed at An Loc in the 1972 siege. (8)

Hanoi was not pleased:

"They [RVNAF] strengthened puppet [sic] forces, consolidated the puppet [sic] government, and established an outpost network and People's Self Defense Force organizations in many villages. They provided more technical equipment for, and increased mobility of, puppet [sic] forces, establishing blocking lines, and created a new defensive and oppressive system in densely populated areas. As a result, they caused many difficulties and inflicted losses on friendly [VC] forces."9

This would not and could not have happened prior to 1968's creation and arming of PSDF with cast-off WWII weapons passed down from main force RVNAF elements. Likewise, the RF/PF, with assistance of US Mobile Advisory Teams (MATs), belatedly employed in 1968 (10), and armed with better weapons, began making progress, as witnessed in 1970 by MAT member David Donovan during a classic infantry assault:

"We had just gotten past the major infestation of booby traps when we began to receive fire from a tree line in front of us. Water spouted up around us, bullets whined overhead, and we heard the stuttered popping of light small arms fire. The men reacted well now, not like the early days when getting any reaction from them under fire was next to impossible. Sergeant Abney took the rear of the column and swung around to the right, using it as a maneuver element while those of us in the front returned fire. When Abney's troops got to a good protected position they stopped and began firing themselves. Under the cover of their fire we moved ahead to yet another position. In this back-and-forth stepwise manner Abney's and my group finally got to the tree line and into the direct assault. Three men in the element I was with had been hit, I didn't know how badly, but everyone kept moving up. We had done well."11

6 Donovan's experience was not unique. Advisor John Cook recalled his optimism of 1970:

"We [Cook and his Viet Namese counterparts] were riding high, feeling almost indestructible. The morale and aggressiveness in the district was extremely high, causing us to pursue the enemy with almost reckless abandonment."12

Performance of this caliber was not universal. There were units that did not respond to changing times and remained plagued by poor leadership, complete absence of aggressive patrolling and tactics, and instances in which American advisors may have been killed, or threatened by, RF/PF counterparts with whom they did not get along.13 Other American advisors did not encounter these unpleasantries but were unimpressed with their advisee charges. Still, accounts of favorable experiences and observations abound, yet are virtually absent from the national discussion and common American perceptions, or what is taught in our schools.

Improvement, or outright excellence, was not limited to the territorial forces, and ARVN infantry divisions-admittedly not all-demonstrated aggressive tactical brilliance. Quang Tri Pacification advisor Richard Stevens, who'd served a prior tour in the Marines, was amazed at the performance of ARVN 1st Division elements successfully attacking an NVA rocket launch site:

"I was totally impressed and just dazzled actually, by the way they operated and by their daring in doings things. ... This was the thirteenth operation like this that this guy [a battalion XO] had led. You're talking about people that are total experts at what they're doing and who have done so many hair-raising things already and are still doing it. ... This regiment's advisors told me all the time I went there that...you're working with the best now. There's nothing we can tell these guys about anything. We're [the advisors] just fire support people. But as far as knowing how to operate, they're the ones that teach us.' We had both Australian and American advisors; they all said the same thing."14

To the south, in MR IV's Dinh Tuong Province, the 7th ARVN division also performed flawlessly, as testified by advisors and US "slick"pilots who flew 7th division troops on combat assaults. While the 7th, perhaps by virtue of the Ap Bac debacle of 1963, was termed by some a "search and avoid"unit, those working directly with the 7th have nothing but praise and admiration for the

7 7th's aggressiveness and tactical expertise. A former NVA infiltrator testified to the ARVN 7th's prowess:

"....the liberated zone was shrinking. ... I spent more and more time moving around, trying to stay away from ARVN operations. "In Ben Tre [AKA Kien Hoa Province] it was mainly the ARVN 7th division that was causing problems. Most of the division was recruited from the Delta so they knew the whole area. They were just as familiar with it as we were."15

Conditions became even worse as newly arrived NVA fillers to "VC"units did not know the area at all and were ill-equipped to wage the tree-line warfare of the northern delta. One POW indicated he was captured shortly after arriving when he and others were assigned to ambush a 7th division sweep the following day. In place before dawn, the would-be ambushers were hit from behind by 7th division flank elements ahead of the main body.16

The results of this became increasingly evident between 1968 and 1971, a period during which US troop strength was reduced by more than half, and decline in VC/NVA offensive operations was clear and distinct:

1968 1972 1968-1972 Change

US Forces 537,000 224,000 Down 312,000/58%

VC/NVA Bn Atks 126 2 Down 124/98%

Small Scale Atks 3,795 2,242 Down 1,553/41%

Terrorist Atks 32,362 22,700 Down 9,662/30%

Assassinations 5,389* 3,573 Down 1,816/34%

Abductions 8,759** 5,006 Down 2,573/43%

Percentage Secure 47 84 Up 37/56% Hamlets

Rice Growing Area 2,296 2,522 Up 226/9.8% (1,000 Hectares)

VN Civilians Admitted to Hospital For War-Related Injuries(% total Population)

88,149 39,402 Down 48,474/55%

VC/NVA Strength 250,300 197,700 Down 52,600/21%

8 *Excludes assassination victims at Hue

**Few abductees ever returned. They are assumed to have been killed.

The disparity of change between VC/NVA strength and offensive actions is illustrative:

Percentage Drop, 1968-1971

VC/NVA Bn. Sized Attacks 98%

Abductions 43%

Small Scale Attacks 41%

Assassinations 34%

Terrorism 30%

VC/NVA Strength 21%

The percentage decline in all forms of VC/NVA offensive operations declined more than did overall strength figures, indicating a decrease in overall military capabilities below that expected from a 21% troop strength drop. This occurred while American troop strength declined 58%. Not only were there fewer VC/NVA in country but they less capable of initiating offensive operations. Little doubt exists that many Viet Nam statistics were of questionable veracity, and the HES rating (secure hamlets) in particular is frequently and justifiably damned for inaccuracies, yet the trend line is clear and there is no body of evidence, statistical or anecdotal, suggesting anything but a precipitous decline in VC/NVA fortunes between 1968 and 1971. While the VC, as distinct from the NVA, were not completely destroyed, and pockets of strong VC influence and control remained in such provinces as Chuong Thien, Dinh Tuong, Quang Nam and Quang Ngai, the indigenous VC were no longer a strategic force and had it not been for massive NVA infiltration and provision of modern weaponry, the war were have gradually expended itself. Even those VC units and areas that remained were entirely dependent on the NVA for their survival. "Anti-war"writer Frances FitzGerald, author of Fire in the Lake (ironically enough thoroughly lambasted by both Hanoi chief ideologue Nguyen Khac Vien and NLF/Hanoi supporter Ngo Vinh Long) acknowledged survival odds for both VC and RVNAF troops, in 1966 was 50-50, yet by 1969 VC survival odds plummeted to 10% while an RVNAF soldier had a 90% survival chance.18 Nguyen Van Thanh, after 23 years as a Viet Cong, defected in 1970, viewing the NLF cause as hopeless, citing improved RVNAF operations,

9 expansion of district PF and PSDF programs, and the GVN's impending land reform program as factors he could no longer deal with.19 Stanley Karnow states forthrightly in his profoundly over-rated book, without ever having explained how this all came about, that by 1971 "...the Viet Cong alone was no match for the Saigon government army."20

Don Colin spent years in Viet Nam and was widely renowned for his gruff, excessively blunt rejection of anything he viewed as, and vociferously damned, as utter bullsh-t. He suffered through the frustrating difficulties, false-starts, and the very same problems viewed as constant unchanging universals, if not harbingers of doom. Yet by 1971 he saw the cumulative results materialize in the delta:

"Thirty months ago the number of good leaders in MR IV could be measured on one hand. Even the corps commander, while he was a good, honest and fairly capable leader, was shy, unimaginative and not capable of stirring his subordinates to aggressive and positive activity. Division commanders were largely incompetent and most Province chiefs were largely incompetent and corrupt. Subordinate commanders not only mirrored but in most case magnified these faults. Now, the overall level of competence, honesty and dedication has risen to levels I would previously have thought unimaginable. ... This particular change has made me more sanguine regarding the ultimate ability of the Government to fully control Viet Nam and establish a stable government."21

Then came Hanoi's 1972 offensive, a conventional blitzkrieg characterized by modern heavy weapons and introduction of such lethal devices as the SA-7 Grail anti-aircraft missile, the AT-3 wire-guided Sagger missile, and a veritable armada of T-54 tanks supported by several hundred 122mm and 130mm artillery pieces, superior to anything and everything in the US-supplied RVNAF artillery arsenal. RVNAF took some heavy hits; it appeared at times as if the end might be near and collapse imminent, yet RVNAF took a standing 8 count, recovered and blunted the heaviest offensive to date in Viet Nam. None other than America's preeminent VN scholar, Douglas Pike, declared Hanoi's invasion failed because "...the South Viet Namese outfought the invaders from the North."22 Many commentators, to include Gen. Ngo Quang Truong, cite American air power as a decisive factor, and it was pivotal. Yet the implication that RVNAF would not or could not fight without US airpower omits

10 consideration of two key points. First, US troops would have expected, and been entitled to, the exact same air power that was used to support RVNAF. Secondly, and this point is seldom recognized: US airpower was a compensatory factor countering both superior NVA armor and, most significantly, superior artillery, the accurate 122mm and 130mm guns delivering massive destruction at ranges up to 19 miles. The US did not provide its ally, the Republic of Viet Nam, with as good an arsenal, especially in the realm of artillery, as the Soviets and Chinese Communist provided Hanoi. Hanoi had hundreds of 122mm and 130mm guns; RVNAF had no artillery sufficient to fire counter-battery, and had only two dozen or so 175mm guns, which are not as accurate as and have a lower cyclic rate of fire than 122s and 130s. Not even reinforced bunkers can withstand 130mm rounds with delayed fuses. Finally, again addressing the subject of airpower, RVN's own air force performed admirably during the 1972 battles, yet remain ignored by American commentators. An American FAC admired the VNAF A-37 pilots with whom he conducted an air strike against NVA positions:

"His dive took him down within range of automatic weapons and sure enough as I saw several lines of tracer ammo arcing toward Pepper lead, I shouted a warning. I saw him release his bombs at the very low altitude and score a perfect hit on the wall. In their succeeding passes, the VNAF pilots scored perfect hits each time and each time they were met by a hail of ground fire. ...ground fire [against the aircraft] was extremely intensive. The North Viet Namese seemed to know their antagonists were South Viet Namese."

"I fully expected the A-37s to be shot down but both delivered all their ordnance unscathed. The two VNAF pilots put on quite a show and I admired their bravery if not their good sense."23

This was not an isolated incident, as attested by another American observer:

"VNAF came into its own during the 1972 offensive. ... In the defense of Kontum the VNAF has been magnificent, absolutely magnificent."24

RVNAF took Hanoi's best shot in 1972, a shot far exceeding '68 Tet battles in terms of troop numbers and firepower. Roughly 150,000 NVA were believed to have been committed in the offensive's first phase, and another 50,000 deployed as the battles ensued. Tet '68 on the other hand, saw 84,000 VC/NVA committed, with limited artillery and armor (excepting MR I).

11 RVNAF continued to do reasonably well after the fraudulent Paris "Peace" Accords were signed and promptly violated. By late September 1973 an RVNAF task force had driven the 1st NVA division out its Seven Mountains redoubt and inflicted such heavy casualties that the 1st was disbanded, its surviving members parceled out to other units. A few months later the ARVN 7th division launched a major operation to drive NVA units out their Tri Phap base area in the Dinh Tuong-Kien Tuong-Kien Phong tri-border area, inflicting heavy casualties. Tri Phap had never been penetrated throughout the war and was characterized by hardened defensive positions; the defeat was so humiliating that communist authorities were cautioned to hide this defeat from their troops lest they become demoralized.25 The Polish and Hungarian delegates to the impotent ICCS (International Commission for Control and Supervision (of the "cease fire")) doubled as spies for the Hanoi's communists. One of their 1973 reports stated no VC units (what few there were) were equal to RVNAF regulars, and even the NVA's best weren't comparable to RVNAF's Airborne or Marines.26

By mid-1974 however US aid cutbacks began to slowly strangle RVNAF, and it would only get worse from thereon out. By 1975 the Available Supply Rates (ASR) for artillery rounds had plummeted to unacceptable low levels (per tube, per day):

1972 1975

105mm 180 10 Down 170/94%

155mm 150 5 Down 145/97%

175mm 30 3 Down 27/90% (27)

Everything was cut to the bone, and into the marrow. Some infantry troops were provided a basic load of 60 M-16 rounds, per week. Some units forbid troops from firing M-16s on full automatic. Infantry units in contact were sometimes limited to two artillery rounds on call unless being overrun. Lack of spare parts forced mothballing of tanks, river patrol boats, and aircraft. Worse yet, RVNAF troops and their families suffered under an economy shredded by 50% inflation and a 25% unemployment rate. A US DAO study conducted in 1974 revealed 82% of RVNAF did not receive enough food to meet family needs.28 Hunger and malnutrition eroded morale and combat capabilities. The